Feature

Horror Puppets

Jason Marc Harris

Puppets and dolls, although wielded as implements of performance—whether playmates of children or personas for theater—remain uncanny vessels of horrific imagination in literature and film.

Many people are familiar with the transmigrated serial killer soul into the doll Chucky, the prop of Billy the puppet in Saw, the deranged portrayal of Anthony Hopkins with the ventriloquist doll Fats in Magic, the troop of grotesque puppets animated by Egyptian magic in PuppetMaster, and—my favorite—the clown doll that leaves its accustomed perch on the bedside chair and ambushes with cackles and a whirling tentacle arm the young boy, who dutifully checks beneath his bed in Poltergeist. Uncanny simulacra of humanity have also appeared in literary works, such as ETA Hoffmann’s “The Sandman” where the romantically idealized woman Olympia turns out to be a mannequin, much to the psychic torment of the protagonist Nathanael. The disorientation that Nathanael experiences characterizes much disconcertion surrounding puppets and dolls. The “uncanny valley” is the key term employed today whereby humans feel more disturbed and fearfully confused the closer a simulacrum of the human form comes to resemble an actual human. The uncanny valley has been a rationale for strategizing the appearance of serviceable robots not to look too human.

In the context of horror, puppet and dolls tend to fall into categories that connect with dread, alienation, and powerlessness. Within the last thirty years, some of the most engaging works dealing with puppets and dolls has come from weird literary horror, such as the short stories of Thomas Ligotti. In “The Clown Puppet” the narrator’s conviction that his entire life has been defined by “outrageous nonsense” is manifested by the intrusion into his life of an “almost life-sized” figure: an “antiquated marionette” that periodically enters his place of employment—a “medicine shop”— with a face fixed with “stupefied viciousness and cruelty.” The clown puppet’s handler remains unknown though the story’s ending hints at cosmic forces to which every person may be subject to but never understand. The narrator’s assumption that the clown puppet is an object manipulated by “wires” is at odds with the expression of “cruelty” that hints at consciousness: “”I always looked at the wires which were attached to the body of the puppet thing [. . .]. It was solely by means of these wires, in my view, that the creature was able to proceed through its familiar motions.” If such a thing as the clown puppet has a consciousness beyond being an extension of distant manipulating powers it is an even deeper subversion of human assumptions of consensus reality than the intimation of unseen rulers and disruptors of human fate. In Ligotti’s “Nethescurial” there are puppets that behave as if reacting autonomously without any indication of being handled by an unseen puppeteer. When the narrator stumbles upon a performance of puppets battling on stage, they stop to stare at him, as do all the people in attendance: there is no clear distinction there between puppets and people, and all perform a chant in sinister obeisance and testament to the omnipresence of the malign entity named “Nethescurial.”

The role of the hapless human—a victim of cosmic and sometimes earthbound sinister forces—figures in many Ligotti’s stories. For example, the young woman sacrificed in “The Last Feast of Harlequin” is described metaphorically as a puppet: “”a limp-limbed effigy, a collapsed puppet sprawled upon the slab.” As a collective mass of humanity “sprawled upon the slab” of existence itself, we are all similarly ineffectual puppets, sacrificed inevitably and totally.

Ligotti employs puppets and dolls and other mannequins in various ways throughout his work, though all are darkly suggestive of human powerlessness and ignorance: the aforementioned puppets in “Nethescurial” give the narrator the stank eye of existential horror; dreams of mannequins undermine a woman’s sense of self in “Dreams of a Mannequin,” and a traveling salesman who indulges his fetish for clown apparel with an aging sex worker is turned into a jester puppet in “The Bells Will Sound Forever. Ligotti’s puppets always carry implications that humans are ultimately incapable of self-determination, their existence has no discernible logic, and the quest to understand what puppet business defines their lives is doomed to bring only dissolution of identity, death—and possibly a variety of fates worse than death.

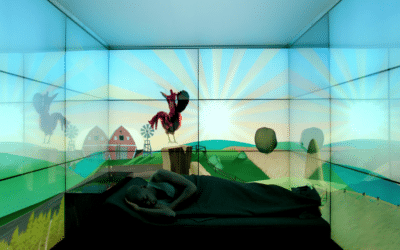

A recent arrival in the ranks of existentially horrific cosmic puppetry is Gemma Files whose “The Puppet Hotel” offers a validation of the protagonist’s conviction that the world is terribly askew, a dynamic reminiscent of Ligotti’s alienated protagonists. Even the first sentence articulates a rather Ligottian cosmic metaphysics: “Sometimes, if we don’t watch out, we might slip inside a crack between moments and see that there’s an ebb and flow under everything we’ve been told is real, a current that moves the world—the invisible strings which pull us, spun from some source we’ll never trace.” The protagonist, Loren, is eventually permitted to peer past the physical barrier of the hotel walls to discern horrific beings manipulating the vestiges of the body and mind of her missing guest: “Her tongue is working the wrong way for the words she’s ‘saying,’ and it looks dry. [ . . .] Like a spider’s web-filaments, tugged on from afar, tempting a fly. Like some invisible puppeteer’s strings” (68). The nameless things that choreograph the grotesque moments of this doomed guest try to entice Loren to join them, but she demurs—not quite so subject a human puppet as to court her own destruction. Gemma Files offers readers a model for resilience despite the specter of inimical puppet masters lurking in their interdimensional webs.

Depictions of human puppetry in horror can be quite literal, such as the brutal tugging at torn tendons to mimic marionette strings orchestrated by Freddy Krueger to the hapless arms and legs of Phillip in A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors. Among horror stories there’s similarly graphic depictions, such as in Richard Kadrey’s Brave Boys Like You where intruders are torn and flayed into new flesh suits for a creepy old man (“You live your life and grow old and when the time is right, you’re reborn in new flesh”) or fashioned into sentinel puppet-dolls.

Storing the soul within an object is an old folkloric motif, and in There is No Place for Sorrow in the Kingdom of Cold Seanan McGuire redeploys this trope as a strategy for managing feelings: “I have called you into being to be a vessel for my sadness, for there is no place for sorrow in the Kingdom of the Cold. Do you accept this burden, little girl, so newly made?” It’s an interesting shift from the assumption that puppets, dolls, and mannequins lack the spark of human emotion. The story also has the intriguing exploration of a Pinocchio-like protagonist who was a fashioned being, part of a legacy of the cold craft. And she takes her vengeance against an abuser.

Puppets, dolls, and mannequins help to also explore the line between what constitutes human identity—what is the thing needful for a truly human soul or at least a human being? If a person can do terrible things and the doll or puppet merely occupy nearby space with an unchanging expression, then how is the person any better than the unfeeling inanimate companion? However, in the mechanics of choice, we see horror creators exploring complications of both mental illness and supernatural metaphysics, as well as the line between autonomy and determinism. Besides the rendering of the schizophrenia of Anthony Hopkins’s ventriloquist in the film Magic, the world of comics has also taken on the disturbing subject though via supernaturalism; the Tales from the Crypt horror comic of the 1950s in issue 12 in the “Witch’s Cauldron” section presented how a ventriloquist can be literally a divided self: the protagonist Charles is persecuted by his evil twin, which has manifested as a head at the end of his arm. The ventriloquist disguises the horror that is his parasitic brother Morty by virtue of makeup and the show of seeming ventriloquism. The ventriloquist “dummy” that flirts with women in the audience eventually ends up killing them, making literal mincemeat of their flesh, and eventually its own host. This comic haunted me as a boy when I read it in a collected volume of EC horror comics. “I’m stronger than you,” I remember the deformed head taunting the ventriloquist, driven to despair by living with the alien in all its tenacious horror. Only death frees poor Charles from Morty.

In Jon Pagett’s “20 Simple Steps to Ventriloquism” an alien intelligence also is a primary feature of the revelation of ventriloquism. The reader eventually recognizes that the second person narration is an inhuman intelligence that mocks humanity as ignorant flesh that can only hope to become yet more explicit vessels for the hostile alien intelligences that control the cosmos and inflict pain as a natural law:

Understand: the throbbing red pulp within and around you is nothing but the barest trifle of the blackness of those horrible cords and pulleys and levers and stitches that hold the universe together—you and your dummy and all those hapless, ignorant animal-dummies out there. [. . .] Now speak in the language of the Ultimate Ventriloquist—that high pitched, hideous glossolalia worming its way up through those exposed, dead lungs and those exposed, dead vocal cords. [. . .] Yes, we Greater Ventriloquists speak with the voice of nature making itself suffer. Nothing could be more normal than that.

It’s a depressing and miserable vision of universal consciousness, but it’s one that resonates with the veil of tears that much of humanity will come to recognize as all too familiar before the stage of life darkens to oblivion.

Surely not all puppets and dolls are demons. I looked forward to the journey to Make-Believe’s lively puppets in Mr. Rogers Neighborhood, and many episodes of the Muppets were not frightful at all, though I sometimes feared Mrs. Piggy might tear Kermit apart in her volatile rage, or that Gonzo might plunge his proboscis into some unwitting victim and deplete them of vital juices. Regardless of the horror, some puppets and dolls are examples of incredible artistry, and the subtlety of their movements achieved only by a lifetime of practice by dedicated puppeteers. Perhaps in that very compelling craft of human mimicry we perceive not only another life, but simultaneously discern an equally meaningful or unmeaningful life. Perhaps puppeteers wonder by what motions they too are moved while their puppets gaze at them with fixed grins and eyes that would not blink at the intelligence that stars explode, worlds burn, or people cry with faces puckering and crumpling while tendons pull and tug in a bundle of inscrutable nerves within.

About the Author

Jason Marc Harris teaches creative writing, folklore, and literature, and is the Creative Writing Coordinator at Texas A&M University in College Station, TX. He graduated with a Ph.D. in English Literature from the University of Washington, and an MFA in fiction from Bowling Green State University, where he served as Fiction Editor of Mid-American Review. Creative work in journals such as Apex and Abyss, Arroyo Literary Review, Bull, Cheap Pop, Marvels and Tales, Masque and Spectacle, Midwestern Gothic, Psychopomp Magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, and Writing Texas. His novella Master of Rods and Strings (Vernacular Books) was released in print and Kindle July 6, 2021 and is included in the Horror Writers Association Bram Stoker Award® Reading List.

Jason reads the opening pages of Master of Rods and Strings here.

And an interview about his novella can be found here.

More Horror

Horror Through the Ages

A Journey Through Time and Terror

Technology in Horror

When gadgets become nightmares

Female Characters in Horror

From Victims to Heroes