Q&A

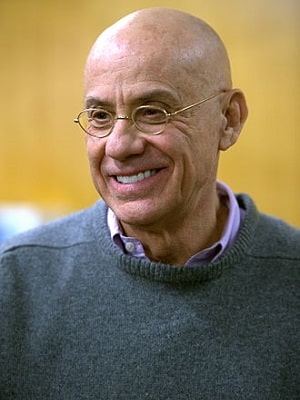

James Ellroy

James Ellroy was born in Los Angeles in 1948. His L.A. Quartet novels—The Black Dahlia, The Big Nowhere, L.A. Confidential, and White Jazz—were international best sellers. His novel American Tabloid was Time magazine’s Best Book (fiction) of 1995; his memoir, My Dark Places, was a Time Best Book of the Year and a New York Times Notable Book for 1996. His novel The Cold Six Thousand was a New York Times Notable Book and a Los Angeles Times Best Book for 2001.

Q. Widespread Panic is a story of the 1950s Hollywood underground. What inspired this one?

James: Years ago, I needed to repay a debt to an editor of mine. She asked me to write a novella. That was the derivation of me going back to Freddy Otash—who I knew in his waning years—who I utilized as a character in the three novels of the Underworld USA trilogy. I crafted a 65-page novella, an origin story. It’s Freddy after WWII going to LAPD and behaving under a dubious moral code and creating panic and getting bounced from LAPD and becoming a private detective and licensed PI. So I utilized elements of Freddy’s real life and fictionalized a great deal. Years later, I realized I could substantially revise Shakedown and turn it into the beginning of a novel, which I did. Part I Shakedown, Part II Perv Dog, and Part III Gonesville, hence Widespread Panic.

Q. Where do you go to research your patois, your jazz slang, and the language that makes 50s Hollywood noir come to life?

James: I make it up. I don’t like research. I have an assistant since I don’t type. I’ve written all my books by hand. And she’ll put together research briefs for me. Absolute factual accuracy means next to nothing to me. I’m out to create what I call an American Tabloid, a reckless verisimilitude. My own semblance of truth. If I think the language fits, I’ll use it. The language in WIDESPREAD PANIC is deliberately hyperbolic because in essence the book is comedy. It’s a very very dark comedy. But in it, Freddy Otash can veer between the extremes of rage, piety, self-pity, grandiosity in the course of two paragraphs. He narrates of course the entire book. But the language I have been lauded for and condemned for is almost entirely of my own invention. And the LA or the Hollywood in Widespread Panic – it’s very much a Hollywood novel more than a crime novel—is of my own wild imagination. There’s really only one rule here: if a writer of fiction wants to portray real life characters in fictional contexts he’d damn well better make sure they’re dead first.

Q. Is that so he doesn’t get sued?

James: That’s exactly right.

Q. The Big Nowhere nails the Hollywood Blacklist. Do you see any parallels between the Blacklist and current cancel culture?

James: Authors have their books cancelled because dicey shit from their past comes up. And I think that that’s wrong unless the person has their day in court and gets convicted of specific crimes. I wouldn’t cancel someone’s book based on unsubstantiated allegations. That’s censorship.

Q. Bringing that back to the Blacklist from the 50s, are there parallels?

James: The Blacklist wasn’t inflicted by the US government, it was inflicted by the studios themselves. You should take a look back at what is commonly called the Red Scare, and when you see the extent to which the International Communist Party and the Communist Party USA tried to infiltrate the culture and disseminate communist propaganda through it, then you might well come to the conclusion that I came to, which is that people hauled up before government committees investigating communist influence in the entertainment industry, well they were the good guys, and the people who refused to testify were the bad guys.

Q. Famously, you have no computer, no internet. Would you describer yourself as a luddite? How does your view on technology affect your writing?

James: I started out in 1979 when I was 30, not quite 31, working as a caddie at Bel Aire Country Club in LA, and I had a $22 a week hotel room at the Westwood Hotel. And I had no desk. When I started writing my first novel, Brown’s Requiem I went out and bought a shitload of college ruled white notebook paper. I had a four-drawer dresser that I leaned down on and wrote standing up. I wrote my first novel and a portion of my second standing up in that manner. Then I moved to another pad that had a breakfast nook so I could write sitting down. But I’ve written 21 books and done a lot of journalism, and written movies and tv shows—I’ve done it all by hand. It’s all I know. I have a fax machine here, I block print still on white notebook paper, all capitals. I’d be hard pressed to write anything other than my name in cursive. And when I edit a manuscript that Alfred A Knopf sends me for one of my books I have to think of what the lowercase printed alphabet looks like. It’s just a particular way that I think. It’s worked for me for over 40 years so I don’t question it.

I’m sitting here at my desk talking to you, I’ve got a landline phone and I’m working on the outline for the new book and I have some research briefs that my assistant prepared. She’ll either FedEx it to me if there’s a lot of pages or she’ll fax it to me if it’s ten or fifteen. And there’s my handwritten notes, and there’s two red, two black pens, a stack of white notebook paper.

Q. Several of your books have been adapted to film: Blood on the Moon (adapted as Cop), L.A. Confidential, Brown’s Requiem, and The Black Dahlia.

James: You want to know what I think of them?

Q. I want to know which is your favorite, but sure, what do you think of them?

James: I think they all suck chihuahua dicks. I think L.A. Confidential is extraordinarily overrated. And The Black Dahlia is a mess. And I don’t care how many awards L.A. Confidential made I think it’s incompetent and I think the actors are impotent. And I don’t care how much they were praised. And it’s a frivolous movie. I will concede its stylishness. And I’ll also go one to say that the magnanimously praised L.A. Confidential only sold 1/50th as many books as the universally reviled movie The Black Dahlia did. It’s money. It’s free money. And that’s that. The books weren’t intended to be made into movies. If any movie studio, film maker, producer wants to come around and option anything that I’ve written that’s ok. Where’s the dough? Money is the gift that no one ever returns.

Q. There are a number of theories on the unsolved murder of Elizabeth Short, ranging from crackpot to conceivable. Do you have any opinion there? Does it matter?

James: No, it doesn’t matter. The person who killed Elizabeth Short is long dead. He’s not going to hurt any more women and that’s that. None of the theories were credible.

Q. What are you working on now?

James: The sequel to Widespread Panic. Tell all your readers to go out and buy this motherfucking book in multiple copies. Don’t read it on the Internet. Hotfoot it over to your local bookseller. It’ll be on sale the 15th.

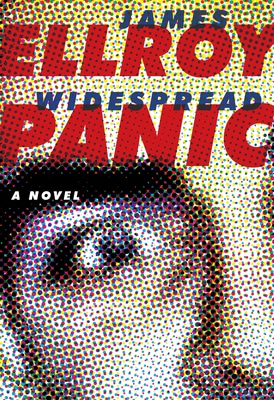

Widespread Panic

Freddy Otash was the man in the know and the man to know in ’50s L.A. He was a rogue cop, a sleazoid private eye, a shakedown artist, a pimp–and, most notably, the head strong-arm goon for Confidential magazine.

Confidential presaged the idiot internet–and delivered the dirt, the dish, the insidious ink, and the scurrilous skank. It mauled misanthropic movie stars, sex-soiled socialites, and putzo politicians. Mattress Jack Kennedy, James Dean, Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster, Liz Taylor, Rock Hudson–Frantic Freddy outed them all. He was the Tattle Tyrant who held Hollywood hostage, and now he’s here to CONFESS.

“I’m consumed with candor and wracked with recollection. I’m revitalized and resurgent. My meshugenah march down memory lane begins NOW.”

More Crime

Advertisement