Nov. 2, 2020

Feature

Locked Room Murder Mysteries

A favorite of the detective mystery subgenre, the locked room murder mystery is here to stay.

It’s one of the oldest tropes in the mystery writer’s toolkit. Someone has been murdered moments earlier, and the killer has to be someone who is present, because nobody has left the room / house / building / boat / plane / spaceship.

Or, someone has been murdered in a room that was locked from the inside and there are no exits and nobody else was in the room. Or, a murder has happened on a train (or airplane) that hasn’t stopped so the killer must still be onboard. Or… Well, actually there are dozens of variations on the trope. Or, maybe seven, depending on whom you ask.

If it’s well-written, the mystery fascinates us because we’re trying to solve the case along with the protagonist (usually a detective or cop). If the author crafts the story well, the reader will have enough clues to solve the puzzle. When we think we’ve figured it out, then pat ourself on the back if we got it right. If we were wrong, but the plot makes sense, we feel oddly satisfied that the author “beat” us, but kept us interested and guessing. If the author drops a bomb on us at the very end where there was no way we could have come up with the surprise based on clues earlier in the book, we feel cheated, but we still might enjoy the read and appreciate the twists. If we figure it out in the first ten chapters, then we’re disappointed.

No matter what, the sub-genre lives on and will continue to be a favorite of mystery writers. It has worked for ninety years, so why stop now?

This isn’t a top-10 list (there are plenty of those). I’m a fan, and while I haven’t written a true locked room mystery myself (yet), I’ll take a few shots here at what’s wrong with some, and what’s great about others.

What makes a great locked room mystery?

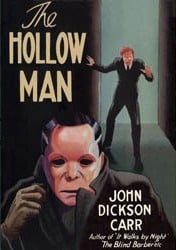

In the classic The Hollow Man, author John Dickson Carr decided to educate his readers by having his protagonist give a lecture on the seven basic types of locked room mysteries. The universe has expanded since 1935, but the basic tropes are mostly still variations on Carr’s original seven. Movie makers used to love the tight plots, confined sets, and “talkie” format of a tight mystery. (And Then There Were None (1945); Murder on the Orient Express (1974); House of Wax (1953) (a horror variation)). In recent years, action, car chases, gunfights, explosions, etc. have dominated films, leaving the locked room mystery feeling like a stage play by comparison.

But, the 2018 major motion picture, Knives Out, brought the genre back to big screen audiences. Laced with humor and an all-star cast, the movie-goer was challenged to figure out how Harlan Thrombey, the aging patriarch (and successful mystery author) was murdered by a letter-opener while inside his private study, alone. All the important members of his family were present that night in the mansion for his birthday party. Nearly all of them had some motive to kill the old man. But who had the opportunity?

Screenwriter Rian Johnson skillfully leaves just enough clues that when detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) finally recites his conclusions about the twisted sequence of events (and the audience gets to see the visual depiction of the “real” events), it all makes sense, and the audience (mostly) says “Oh, yeah.”

Knives Out is entertaining throughout, and the ultimate reveal is fully logical and consistent with everything that came before – even though the path to the truth was as curvy as it gets. Hence, entertaining and satisfying. Well done.

Knives Out relies on one of the seven historically basic tropes (though we won’t tell you which). As explained by Carr’s Dr. Fell in 1935, these are:

- The death was actually accidental, so there was no murderer who needed to escape from the unescapable space.

- The lethal weapon was poison (gas or otherwise) so that the murderer was not really there.

- The death was caused by a booby-trap so (again) the murderer was not really there.

- The murderer impersonated the victim.

- The victim killed himself.

- The kill is accomplished from outside the room using a disappearing murder weapon (an ice-knife or ice bullet), disguising the possibility of an extra-territorial cause.

- The victim wasn’t really dead until the killer entered the room along with the police or other witnesses, at which time the killer executed the murder, making it seem like it happened earlier.

Even imperfect examples of the locked room mystery can still be popular

A less well-constructed, but wildly popular, recent example is Ruth Ware’s best-seller, The Woman in Cabin 10. Here, the events on the boat (which could be characterized as either a large yacht or a very small and exclusive cruise ship) posed not only the question of who done it, but first whether there was, in fact, a murder at all. That was a clever idea – leaving the reader wondering whether the first person narrator, a journalist named Lo, hallucinated the whole thing, or whether there really was a murder. The trope here was impersonation – the person who was killed seemed to be alive. When Lo tries to tell the other passengers that she thinks she witnessed a murder, there’s nobody missing. It was a potentially brilliant variation, leaving all the other passengers aboard the boat as possible suspects (if there was a murder).

Unfortunately, Ms. Ware’s execution was sloppy, sending the reader down several blind alleys and leaving far too many loose ends. Although there were a few clues dropped in to help the reader (in retrospect) see how the imposter could have been identified, the logic of what “really” happened never makes sense. Still, it was a gripping read and the author generated tension and suspense that kept me riding along until the end. The book was hugely successful – a credit to both the author and the publisher’s marketing efforts. But, this is one that could have been better. (Feel free to disagree with me, but if you do, explain to me how Richard needed an alibi for the time when the murder was not committed, and why he didn’t just toss his wife’s body overboard himself from the comfort of cabin one, instead of . . . oh, don’t get me started.)

Let’s retire a few of the locked room mystery tropes

For my money, the locked room mystery is still a winner – in most cases. Even a bad one can still be fun and worth reading. Those of us who grew up on Encyclopedia Brown and Nancy Drew will always find enjoyment from these stories, even the ones we want to throw against the wall. There are a few tropes that might be better off left on the historical shelf, however, including:

The Supernatural

The answer is something magical or supernatural (the ghost did it). Unless you’re an author of a paranormal series and your audience expects there to be a paranormal explanation, this is the equivalent of “it was all just a dream.” If the answer to the impossible murder is that it really was impossible, except for someone with powers to change the laws of physics, then it’s not satisfying.

Suspension of Disbelief

There is a virtually impossible explanation that, while logically consistent, requires such suspension of reality that it’s not plausible (see “Murders in the Rue Morgue”). I can live with the explanation that the killer spent ten years in the circus learning to be a sword swallower and was able to hide the murder weapon in his throat. But I’ll draw the line at the plot where the murderer spent ten days training his parrot to pull the cord that fired the hidden gun at the exact right moment. Sure, if it happened that way it would explain everything, but . . . c’mon.

Footprint Clichés

The lack of footprints in the snow as the main puzzle. It’s been done too many times. The window is the only point of entry, but it’s “impossible” for someone to have climbed in and out without leaving tracks. At this point, we all know it’s not impossible, so it’s not that mysterious.

Melting Evidence Clichés

The ice knife/ice bullet that melts away after the murder. Modern forensics would not be so easily fooled. And don’t give me a plastic gun made by a 3D printer, either – at least not one that fires hundreds of accurate rounds from long distance.

Where do we go from here?

The basic locked room concept is still compelling. In almost all examples, there is a large cast of suspects, whose characters can be developed by the author in many creative ways. The plot becomes the glue allowing for unlimited character-driven subplots. There’s a murder to solve, and plenty of room for action, conflict, twists, and ultimately resolution. It’s used often because it works. Horror films re-use the arm that comes out of nowhere holding the knife – accompanied by the Psycho-inspired high violin screech music – because it still works. Hitchcock was a genius, so why not copy him? The same goes for John Dickson Carr. Imitation is the greatest form of flattery.

In Locked Room Murders and Other Impossible Crimes: A Comprehensive Bibliography, Robert Adey in 1992 added thirteen more “standard” tropes that have evolved over the years since 1935. (Go read it yourself to see the list, this isn’t a Masters course.) You can quibble about whether the additional thirteen are really just variations on the original seven, but as new authors try their hands at variations on the theme, we’re bound to come up with a few original ideas. That’s the fun of reading and writing them – trying to solve new puzzles, and trying to come up with new puzzles to be solved. Coming up with a new twist on an old plot is the mystery writer’s brick and mortar. (Let’s face it, there are only so many ways you can kill someone.)

As technology continues to evolve, writers will have even more potential explanations for “impossible” events. Remote-controlled devices linked to smart phones, drones (that fly in the window and fire the kill shot without leaving tracks in the snow), microchip implants that can cause heart attacks, and Wi-Fi-based signals can all be used to spin out unique plots. Will anyone will come up with a variation that can’t be forced into one of the existing 7 (or 20) boxes? We’ll have to keep reading to find out.

About the Author

Kevin G. Chapman is a full-time attorney and a part-time crime-fiction author. His current Mike Stoneman Thriller series has been recognized for excellence in the Kindle Book Award and the Chanticleer International Book Award competitions. The Kindle edition of Book #1 in the series, Righteous Assassin, is available FREE from Nov. 2 – 6. The next installment, titled Lethal Voyage, launches November 22, 2020 and is available now for pre-order.

Kevin is a resident of West Windsor, New Jersey and is a graduate of Columbia College (‘83), where he was a classmate of Barack Obama, and Boston University School of Law. Readers can contact Kevin via his website at www.KevinGChapman.com.

More Detective Mystery Articles and Reviews

Invisible Helix

The body of a young man is found floating in Tokyo Bay

Perfect Storm

They bring back the widow of a recently murdered man

The Solstice

Rumors that he was sacrificed in a midsummer ritual resurface