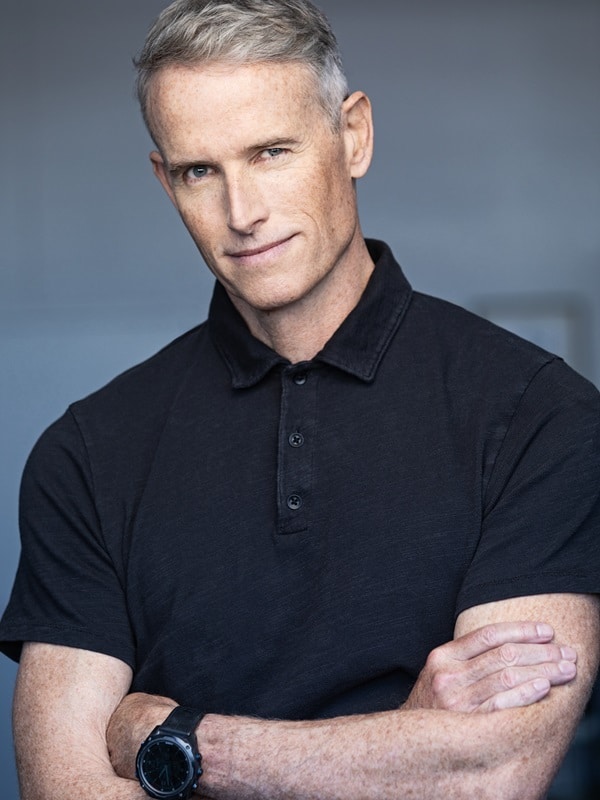

ABC News legal analyst Matt Murphy spent twenty-six years in the Orange County, California, District Attorney’s Office with seventeen years in the Homicide Division. He prosecuted the worst of the worst offenders for heinous crimes and never lost a case. Retired from the DA’s office, he is currently a practicing defense attorney, avid surfer, and a hero to families of victims of the killers he prosecuted. Murphy is seen in multiple true crime documentaries, podcasts, and is a popular presenter at CrimeCon events. His first book, The Book of Murder: A Prosecutor’s Journey Through Love and Death provides a close look at the role of a homicide prosecutor from call out to the crime scene through conviction of the defendant. Readers may recognize some of the cases covered. In addition to delving into cases, Murphy provides a glimpse into the effect of the job on a prosecutor’s personal life and reader education on the legal process.

Interview by Judith Erwin

Q: What made you decide to write The Book of Murder?

Matt: That goes back to CrimeCon. I’d done five “no body” homicide prosecutions to verdict. Kelly McLear, who along with Kevin Balfe, runs CrimeCon, asked me to do a presentation on prosecuting “no body” cases.

The crowd was wonderful. There was no defense lawyer objecting to anything I said. I didn’t have to be right. There was no judge looking at me sternly. I had a lot of fun with it. And then I got a call at two a.m. when CrimeCon was basically over. They’d just gotten the audience reviews. Kelly said, “You got a perfect ten. You have to write a book.”

That’s how it started. I got a literary agent named David Larabel, who I love to death, and he hooked me up with a real pro named Jeremy Blachman, and he helped me put it together, because I had no idea how to write a book. I would write sort of tin can paragraphs, and he would turn them into gold. It wound up being a really fun experience. In fact, I probably had too much fun because I’ve decided we’re gonna come in with another proposal on serial killers for the next one.

Q: Did you always want to be a lawyer?

Matt: I did not always want to be a lawyer. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. [In college] I knew that I wasn’t ready to move off the beach and stop surfing yet. We had an allegation of hazing in my fraternity. It was my first taste of the legal process. I had to navigate this thing, and it was a kick. I got the house through it. I wasn’t ready to join the workforce… and had a bunch of buddies going to law school. I’m terrible at math, so, it all came together.

Q: How did you decide which area of law to pursue?

Matt: I was looking at a bunch of big civil firms. I was recruited by a plaintiff’s firm and by the FBI. They liked me and I liked them. But then, also, by a woman named Kathy Harper at the Orange County DA’s office.

The FBI, back then, wouldn’t assign you to a city where you grew up, where you went to college, or where you went to law school. So, for me, that took me out of Southern California, which is the only place then that I wanted to live. The civil guys also offered me a position, but I decided to take the clerkship at the DA’s office. My plan was to be a DA for three years.

I knew at the end of my very first day as a junior law clerk in 1992 that I’d found my home. I absolutely loved it, and all I wanted to do from that day forward was to be a DA.

Q: Was Homicide always your goal?

Matt: You start out in misdemeanors. Then you get a little more skilled and start doing more trials. It gets to be more fun and more interesting. The longer you stay, the better the cases get. Pretty soon you do felonies, and you’re dealing with what you think are the big boys. And then they move you into what’s called a vertical unit in Orange County, where they give you your own investigators. You’re assigned your cities, and you’re working with the same cops. I went to sexual assault. My three-year-plan turned into twenty-six years, and it just kept getting more and more interesting. I spent the last seventeen in the Homicide Unit and had the cities of Newport Beach, Costa Mesa, Laguna Beach, and Irvine. Any murders that happened in those cities were automatically mine. I’d get a call from the detectives in the middle of the night, because for some reason everybody kills each other at three in the morning.

Q: Can you describe the role of a homicide prosecutor?

Matt: We’d roll to the crime scene. The prosecutors are there to help the detectives with anything they need, to make sure the case is investigated properly with no mistakes made, and to make sure the warrants are done properly and all that.

The prosecutor decides who gets charged, with what, and when there’s enough evidence. The detective assigned to the case is with you all the way through. That’s where the vertical comes from. The prosecutor is there the night of the murder, and the lead detective is there with the prosecutor through the end of trial and into sentencing.

Q: In the book, you give the reader a close look at murder trials of terrible killers. Which do you consider the worst?

Matt: That’s a question I’ve had before, and it’s a tough one to answer, because there’s almost different categories, different kinds of murder. There are child abuse cases where you just can’t believe you’re looking at a child. Samantha Runnion was a tough one, because it was Alejandro Avila, who kidnapped, raped, and murdered a five-year-old girl. That one was absolutely horrific. He had been acquitted of two child molestation cases in Riverside County the year before, so that one was absolutely heartbreaking because it was a result of prosecutorial failure.

Rodney Alcala [a/k/a The Dating Game Killer] was tough for the same reason. He’d been prosecuted for the kidnapping of an eight-year-old, named Tali Shapiro, in 1968. He did thirty-four months in a California State prison, and they released him. He probably killed one hundred people after that. That one was tough because he was so brutal with his victims, and it was so preventable.

I did several that were like ten on the Richter scale. As the prosecutor and shot caller, when you encounter a case that’s truly disturbing, those are the ones you lose sleep over. You have a couple of good detectives and a little bit of time. I had a very supportive district attorney who gave me the latitude and the support I needed and the resources. As a prosecutor, you know, in a weird way as disturbing as it is, you have power over the outcome. A good prosecutor will take those things to heart. When you meet with the family, and your heart breaks, you are in the unique position to be able to do something about it. It was that feeling of being able to set things right to the greatest degree and deliver justice to a few families—that’s what kept me in the DA’s office, past my three-year plan and for twenty-six.

Murder trials in Southern California are like open warfare. There’s a lot of good defense lawyers, and you’re up against well-funded defense teams. You’re working with the same detectives, so, you build up a relationship of trust. You wind up with a mystery you’ve basically got to solve together.

After about five or six years, I volunteered to be one of the two cold case deputies in the Orange County Homicide Unit. It gave me the ability to prosecute cases from around the county other DAs had taken a pass on and to meet families denied justice. A lot of cold cases are just DNA hits. The interesting ones are where you know who did it, but some prosecutor back in the day felt like there wasn’t enough evidence. For lack of better terms, it was the coolest thing I’ve ever gotten to do in my life—the opportunity to dust off some of the old boxes and do a deep dive. It’s like a time capsule with some of them back to the 1970s. You’ve got a suspect, and you look through to figure out if there is something we can test? Or sometimes it’s just a new set of eyes.

Q: In the beginning of each trial, what was your biggest fear?

Matt: In Orange County, it takes a while for murders to come to trial. So that’s a long time to get to know the family—to get to know the bereaved mother. Everybody’s got a mom, especially the younger victims. And you just don’t want to let them down. That’s the biggest fear. Of course, you don’t want to let a murderer get away with it. When it comes to the serial killers, the pressure is that you know they’re going to go out and do it again if you lose. I would always meet with the family. I would always give the family my personal cell phone number, but the downside of that is when you get to trial, they’re really depending on you. The idea of letting them down, I couldn’t imagine. You know the only thing worse than losing a loved one to murder is losing a loved one to a murderer who gets away with it.

Q: Speaking of post-trial moments, you describe a chilling moment in your book that occurred after the verdict in the Ed Shin case when the victim’s brother came to you.

Matt: I can still feel it. He gave me a hug. He was crying, and I can still feel the stubble on my face. It’s incredibly rewarding. I wouldn’t have had that in a civil firm.

Review by Judith Erwin

The Book of Murder: A Prosecutor’s Journey Through Love and Death takes the reader through the author’s career as a Senior Deputy District Attorney in the Homicide Unit, Orange County, California, opening with Murphy en route to his first homicide scene, haunted by thoughts of a failed personal relationship. Fresh out of four years in the Sexual Assault Unit, he is no stranger to the evil and brutality of the criminal mind.

As Murphy describes the murder cases he prosecuted, always obtaining the desired verdict, he provides an informative look at investigations, legal procedures, case development, and trial strategies without overlooking the human factors involved. From the heinous rape and murder of children by serial killers to a bizarre case of torture, Murphy reveals the compassion and dedication of law enforcement and the lawyers he worked with and admired. Sprinkled throughout are some of the memorable quotes of one of his mentors, Lew Rosenblum. When discussing the difficulties of trying a “no body” case, where the prosecution is charged with proving that a human being was killed, Rosenblum said, “The jury sees the soul of your victim reflected in the eyes of those who loved them.”

The case of The Dating Game Killer, Rodney Alcala, covered in the book, is the basis for the feature film Woman of the Hour, and the John Meehan case was made into a TV series, Dirty John. The latter being a case Murphy took pleasure in clearing Terra Newell of wrongdoing and motivated him to include in the book a red-flag checklist for those engaging in online dating.

Overall, the book successfully blends true accounts of crime-solving with a bit of legal education and a feel for those who serve and protect society in a manner enjoyable to read.