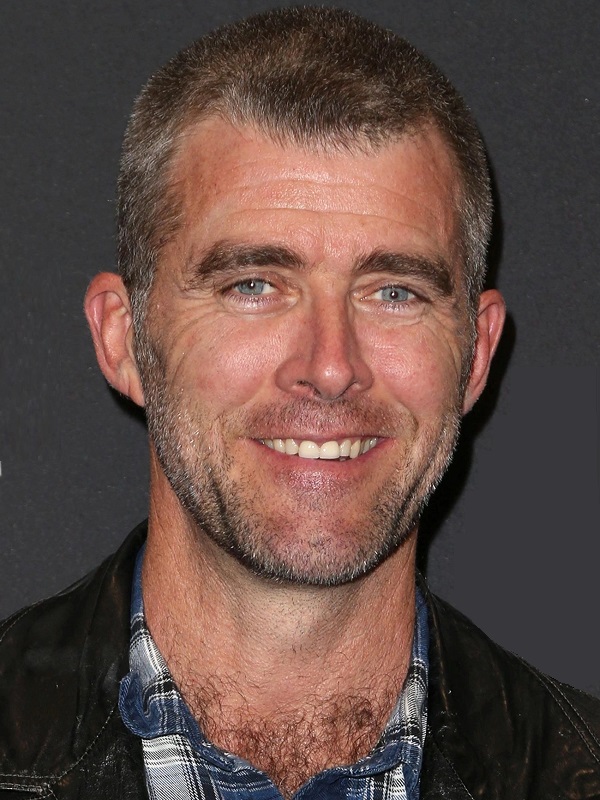

Q&A

Paul Scheuring

PAUL T. SCHEURING has been a working writer, director, and producer for Hollywood since 1999. He has written numerous projects for film and TV, including FOX’s popular Prison Break, A Man Apart starring Vin Diesel, and Den of Thieves. He wrote and directed The Experiment starring Academy Award winners Adrien Brody and Forest Whitaker, and served as a producer alongside Ridley Scott on Klondike, a series he created and co-wrote. Scheuring lives in Northern California with his wife and two children. The Resurrectionist is his second novel.

Q What is The Resurrectionist about?

Paul: The Resurrectionist centers on the bodysnatching business that swept through London in the early 19th century. I wanted to tell the story from the inside—from the perspective of one of the grave robbers, as I found the practice so repellent that I was curious as to who would actually engage in it. Through research, I found that often it was a source of quick income for the working class—a bit like the gig economy today. One night’s work in a cemetery could gain a working man much needed funds, even if it was in digging up corpses.

Q What inspired you to write a gothic horror novel?

Paul: I think the practice of bodysnatching naturally lends itself to both gothic and horror! At the same time, I wanted to tell a very human story of a single father that would engage in the desperate and repugnant business, if only to secure a better future for his daughter.

Q What are some of your favorite stories in this genre?

Paul: I cannot think of a more astounding work of literature than Frankenstein. What Mary Shelley did at the exquisitely young age still dumbfounds me today. It works on every level.

Q Your breakout success was with the hit television show Prison Break. Can you talk about your creative process for developing the concept and characters for the show?

Paul: Like Resurrectionist, I was fascinated by the human element behind the larger conceit. Yes, we need to have one man get himself—willingly—inserted into a prison to break out another. But I had to know why—in a believable way—anyone would do such a thing. Ultimately it came down to family. Either I save my brother or he dies. Once I unlocked that, the rest of the plot fell into place.

Q The show had a large and dedicated fan base. How did you balance the fans’ expectations with your creative vision for the show? And how does that compare to the novel writing process?

Paul: The creative process remains mysterious to me. I suppose I should say…you never know what will land with the audience. All you can do is do the best you can, do a ton of research, and leave it all on the field. If it fascinates you, it has a chance to fascinate the audience. But again, the whims of the larger audience are impossible to predict, so in my opinion it’s a fool’s errand to tailor your work to ‘what the audience’ will respond to. Plus, you feel like a hack when you do that.

Q What does suspense in storytelling look like to you?

Paul: I remember, upon Prison Break‘s big debut, being emailed by a show runner of another big show, who suggested we get together and discuss the ‘art of the stall’. By this I presume he meant how to perpetually tease the audience in TV—in other words, never getting to the heart of the matter. I didn’t end up meeting with him, because that’s not how I create stories. Whether it’s film, TV, or novels, I need to know where everything ends before I start. In general, I tend to come up with the premise, then immediately in my mind ask ‘Okay, then how must it end?’ I use ‘must’ here in a poetic or Shakespearean sense. What is the most elegant way the stories must end if we are true to the characters. It’s sort of a bookend or barbell approach: “Ah, I like that set-up. Now what’s the end?” After that, it’s just filling in the stops on the journey in between.

Q What can fans expect from your future projects, and what kind of stories do you hope to tell in the future?

Paul: I try to tell new stories. The Resurrectionist, crudely put, is a heist in a cemetery. I don’t think such a thing’s been done before, at least in abstract. Nobody needs a reheat of anything. The modern audience is so steeped in narrative–even my 9-year-old sees through all cliches. Most importantly, it has to feel true when creating it. When you’re prostituting yourself, you know it. As I mentioned earlier, you have to fascinate, move, and occasionally amaze yourself in the conceptualization, research and execution of your work. If it feels fresh to you, it most likely will feel the same to everyone else. At present, I’m deep into the research and writing of two additional gothic stories–one in the world of Spiritualism and seances in 1886, the other in 1849 Egypt, centering around the first Englishmen to go up the Nile as tourists (and armchair tomb hunters). What comes out of deep research are new ways to tell old stories. Most stories we see today use the previous canon of their genre as source material. When you go to primary sources, in that research library sense, you find a lot of cool stuff that hasn’t been done before.