Feature

Revenge and the Thriller

Eric Dezenhall

The impulse for revenge is in all of us. Maybe we don’t admit it. Maybe we don’t act on it. But it’s there, below the surface, waiting to strike when we’re mistreated, maligned, or betrayed.

In Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, the killer turns out to be everybody. Why? Revenge.

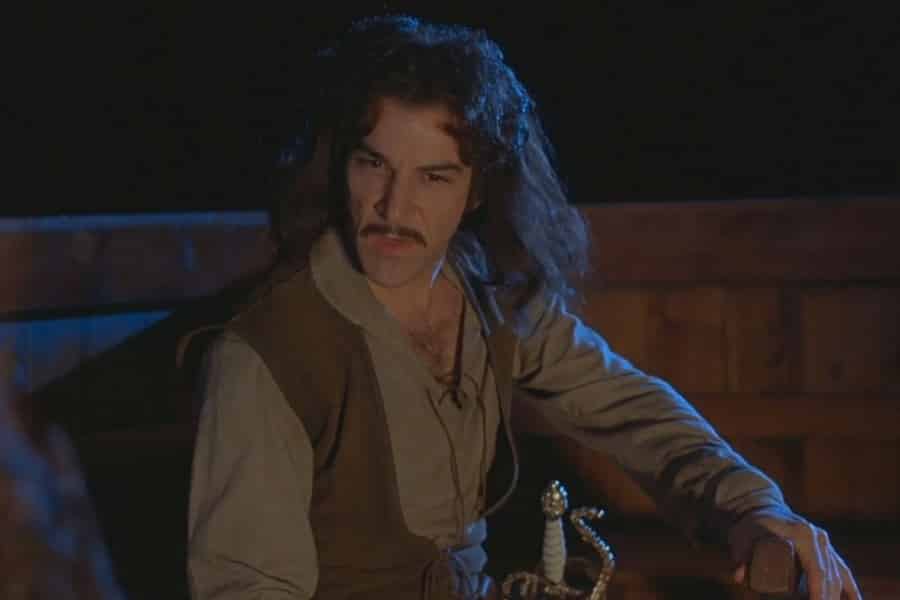

In William Goldman’s The Princess Bride, Inigo Montoya’s thirst for vengeance over his father’s murder is oddly sweet, especially when combined with the panache of his swordsmanship. In Charles Portis’ True Grit, we root for a fourteen-year-old girl, Mattie Ross, who willfully charges into the Western frontier occupied by roughnecks and killers to avenge the death of her father. In Elmore Leonard’s lesser-known Gold Coast, an aging but seductive mob widow, Karen DiCilia, concocts what is essentially a war on slobbering men just for her own amusement. And then there is The Sting, a film where two con men avenge the death of a cohort by swindling a fortune from a gangster with no redeemable human qualities.

All of them, tales of revenge.

But why do we care so much about revenge? After all, we know we’re not supposed to.

It comes down to one thing. Humiliation.

We even root for monsters to get revenge if we feel they have been humiliated. Think of what The Silence of the Lambs’ (Thomas Harris) Dr. Chilton does to the homicidal cannibal, Dr. Hannibal Lecter in prison: strapping him into gothic restraints, keeping him in a dungeon, taking away his eating utensils and his art supplies. Never mind that Lecter richly deserves to suffer these indignities. There is something about Chilton’s smug gloating and credit-taking that makes us want Lecter to make a buffet out of him. We therefore cheer Lecter as he follows a terrified Chilton to a Caribbean island where, in the film, he says goodbye to Clarice by purring he’s “having an old friend for dinner.”

There is a reason subordinate to humiliation for our fascination with revenge: a primal desire for the world to balance out a little more. Most of us know someone who habitually gets away with things or is otherwise lucky. Perhaps the hardest lesson most of us learn – and learn really hard – is that life isn’t fair. Revenge, or at least organic comeuppance, is a way of restoring order so that we can climb out of bed in the morning and face the universe.

Revenge in thrillers amuses us in large measure because we know we’ll never do it, either because of our own moral structure, legal constraints, or practical limitations. I remember fantasizing about administering a devastating roundhouse kick to a school bully in seventh grade – and watching pretty girls cheer me on. Around that time, I even dreamed about a persistent rival watching TV to see me sworn in as President of the United States. Like revenge fantasies, self-delusion is a temporary painkiller.

The best form of revenge involves using a tormenter’s weakness against him. In The Sting, the gangster, Lonegan, is ensnared by his own greed after Paul Newman’s Gondorf pierces his vanity by consistently mispronouncing his name (Ah, there’s that insignificance again). In False Light, a sexual predator’s addiction to publicity is the cheese in the mousetrap.

But most revenge narratives possess a big flaw: The target of revenge knows precisely who did it to him and is in a position to retaliate. This is perhaps the essential flaw in The Godfather novel and movie. Does anyone believe that the thousands of murderers that comprise the four other crime families, the leaders of which Michael Corleone annihilated, are going to throw up their arms and say, “Oh, well, I guess Mike won,” and then just go out quietly for some linguini puttanesca?

In any case, revenge in thrillers is here to stay. As long as most of us remain civilized and without a predilection for executing vengeance campaigns, there will surely be a market for fiction that makes us feel a little hope that the world balances out.

About the Author

Eric Dezenhall is the author of eleven books, including his new novel, False Light. His last book, a work of non-fiction (with Gus Russo) is Best of Enemies: The Last Great Spy Story of the Cold War. He is also the CEO of Dezenhall Resources, Ltd., a crisis management firm based in Washington, DC.

More Thriller Features

Hiding Bodies

The sinister act of hiding bodies in thrillers

Morally Compromised Thrillers

Right, Wrong, and Everything in Between

Family Dynamics in Thrillers

The Most Unusual Family Dynamics in Thriller Fiction

Advertisement