The Morality of Shapeshifters

Shapeshifters. They creep through the annals of horror lore, lurking in the shadows of our darkest fantasies. These masters of masquerade have long captivated our imaginations, from ancient myths to the silver screen, but the burning question remains—do they deserve the label of evil?

Flip through the dusty pages of folklore, and you’ll find these creatures are as old as storytelling itself. The concept of humans transforming into animals, or vice versa, pops up in cultures all over the globe. Native American legends speak of skin-walkers, beings who could don the pelts of animals to harness their powers and traits. Across the pond, European tales often warned of werewolves, humans cursed to become wolves, typically at the pull of the full moon’s puppet strings.

These early shapeshifters often teetered on the brink of malevolence, their abilities usually a curse rather than a gift. But were they inherently evil? The answer isn’t as clear-cut as a silver bullet. Take the case of the werewolf: while some stories painted them as mindless beasts, slaves to their own primal urges, others portrayed them as tragic figures, struggling against their nature, fighting tooth and claw to retain their humanity.

Moving from the campfire to the library, literature has had a field day with shapeshifters. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, penned by Robert Louis Stevenson, presents a literal transformation from good to evil within the same man, an allegory for the dual nature of humanity. Then there’s Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis,” where the protagonist, Gregor Samsa, wakes up one morning to find himself inexplicably transformed into a gigantic insect. Here, the horror lies not in what Gregor does, but in the alienation he experiences as a result of his transformation.

The novel “Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter” series by Laurell K. Hamilton throws a curveball into the mix with its blend of the erotic and the supernatural, featuring shapeshifters as complex characters with their own cultures, hierarchies, and moral compasses. And let’s not overlook “The Shapeshifting Detective,” where the protagonist uses their ability to solve crimes. Evil? Not quite. Misunderstood might be the apt descriptor here.

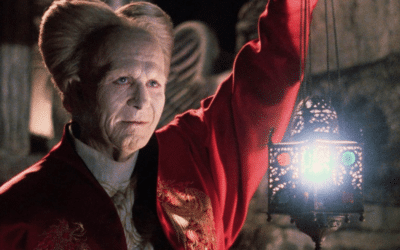

Cinema, that dazzling dream factory, hasn’t been shy about inviting shapeshifters to the dance, either. John Carpenter’s “The Thing” is a masterclass in paranoia, a shape-shifting alien infiltrating a remote research station in Antarctica, its true form a mystery. The creature’s goal is survival at any cost, but does that equate to evil, or is it simply nature’s cold, indifferent survival instinct in action?

In the world of animation, “Spirited Away” by Studio Ghibli presents a more nuanced view of shapeshifting. The film’s characters, like the enigmatic Haku and the witch Yubaba, change forms in ways that serve purposes beyond simple good and evil, instead reflecting their complex identities and the shifting nature of the world around them.

But let’s cut to the chase. Not all shapeshifters are designed with a redeeming arc. “Animorphs,” the children’s book series and television show, may appear to be a simple tale of kids with the power to morph into animals, but it’s laced with the psychological horror of losing oneself, the threat of becoming trapped in another form—a stark metaphor for losing one’s identity.

The small screen has been particularly kind to our metamorphic friends. “Supernatural,” the long-running television series, often portrayed shapeshifters as monsters, but ones that could be as varied in motivation and morality as any human. Some episodes peeled back the monster-of-the-week veneer, exploring the tragedy of beings caught between worlds, neither fully one thing nor the other.

Then there’s “True Blood,” the series that put a southern Gothic spin on vampires, werewolves, and all manner of shapeshifters. In Bon Temps, Louisiana, shapeshifters are just another marginalized group, striving for acceptance and grappling with their own demons—both literal and figurative.

Are shapeshifters evil? The closer one looks, the blurrier the line becomes. They are chameleons of the narrative world, their morality often a reflection of the society that creates them. For every bloodthirsty beast prowling through the pages or across the screen, there’s another fighting to retain their humanity, to use their gifts for some greater good—or at least to avoid becoming the monster others expect them to be.

Consider the award-winning “The Shape of Water,” Guillermo del Toro’s cinematic love letter to the misunderstood monster. The film’s Amphibian Man is a shapeshifter of sorts, a creature capable of changing his biology, his abilities shifting with the plot’s demands. Is he evil? Far from it; he’s the hero of the tale, a silent guardian in a world that views him as an abomination.

Even in the annals of comic books, shapeshifters defy easy categorization. Mystique from the X-Men universe is a prime example. She’s been a villain, a hero, a mother, a fighter—a shapeshifter in every sense, her allegiances and actions as mutable as her physical form.

Perhaps the true nature of shapeshifters is not in the question of whether they are evil, but in their embodiment of change. They are the ultimate outsiders, beings who by their very nature challenge the status quo. In a world that often fears change, shapeshifters hold up a mirror—sometimes quite literally—to our own prejudices, our own fears, our own potential for both good and evil.

So the verdict on shapeshifters? It’s a resounding “depends on who’s telling the story.” The beauty of these creatures lies in their complexity, their ability to be heroes, villains, or something altogether more enigmatic. Shapeshifters will continue to be a fixture in horror and fantasy, not because they are evil, but because they are us—our hopes, our fears, our duality—wrapped in a mystery, cloaked in the guise of the other.

From folklore to modern fantasy, shapeshifters walk the line between the known and the unknowable, the light and the dark. They are the monsters we fear in the night, and the heroes we hope will save us at the break of dawn. Their stories are as varied as their forms, a spectrum of morality played out in tales designed to thrill, to challenge, and to reflect the ever-shifting nature of the human soul.

More Monster Features

Monster Horror Adaptations

The best monster horror film and television adaptations

Father of Monsters

Junior Laemmle – The Forgotten Father of Monsters

Monsters of Horror

Why We Love The Big Baddies Of Horror