The Villains of True Crime

by John David Bethel

“One side of me says, I’d like to talk to her, date her. The other side of me says, I wonder what her head would look like on a stick?”

How do you deal with that? How do you make sense of it? You don’t because you can’t.

This quote comes from Edward Kemper. He killed six women and capped off his reign of terror by murdering and decapitating his mother, and doing unspeakable things to her corpse.

“You feel the last bit of breath leaving their body. You’re looking into their eyes. A person in that situation is God!”

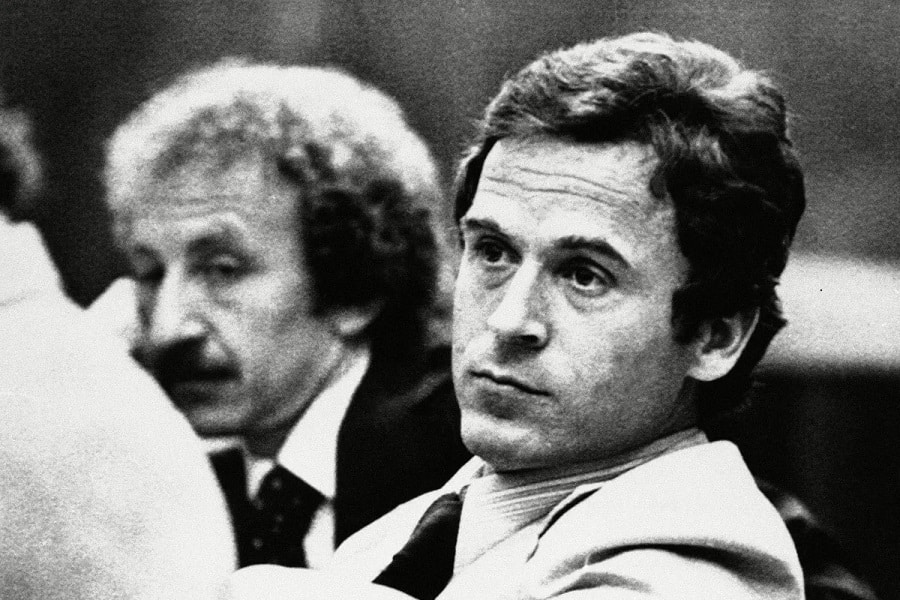

The man who said this kidnapped, raped, and murdered at least 30 women across seven states although his true victim count is thought to be much higher. The speaker, Ted Bundy, like Kemper, was a highly intelligent, educated and – according to people who knew him – a very likable person. Kemper was a regular at a bar that catered to cops and he was accepted by the patrons as one of the gang.

John Douglas, the legendary FBI criminal profiler, and one of the foremost experts and investigators of criminal minds and motivation, has said: “Normal people find it difficult to grasp the reality that predators really do think differently. We tend to want to evaluate them from the point of view of our own experience and life values.” Unless one has thoughts and experiences similar to Kemper, Bundy and others, how can any of it be made understandable?

Dr. Stanton Samenow, a psychologist who studied criminal behavior concluded that “criminals think differently from responsible people.” Criminal behavior, Samenow posits, is not so much a question of mental illness as a character defect.

A criminal psychologist might not define this “character defect” in simple terms, but others might call it “evil.”

Bundy and Kemper grew up in broken homes, as many children do. Kemper’s mother was by all accounts something of a shrew and was harsh on her only son. Bundy was handed back and forth from grandparents to other relatives in his early years. When his mother married, he was adopted by his stepfather and lived in a family unit with other siblings. Neither Kemper nor Bundy were sexually abused, mistreated, or abandoned as youngsters. There are, of course, histories of violent men and women whose behavior is often ascribed to those troubles. But there are millions upon millions of people who had unfortunate upbringings and did not go on to lives of unspeakable violence.

Character defect? Evil.

Then there is violence on a scale so huge and vile it is denied as impossible when being inflicted and declared incomprehensible when discovered. The Holocaust engineered by Hitler and his henchmen. More than six million killed in concentration camps and gas chambers. During this same period, Stalin was ordering the execution of millions of people he considered threats to him personally or to the communist regime. Millions more died in Russian prisons, or of famine brought on by ill-conceived government programs.

Character defect? Evil.

There is certainly grist in all this mayhem for the writer, but how can it be dealt with believably or effectively or honestly? Is it possible to offer the reader an understanding of the violence, the chaos, the pain and mayhem caused by people like Bundy and Kemper, by men so monstrous that millions die on their watch?

One of the attractions of writing is the ability to create a world, people it with characters of all shapes, sizes, abilities, faults and strengths, and then explain the impact they have on themselves and on others. In doing so, writers help us understand human nature and, possibly, understand ourselves. A bit broad, perhaps even presumptuous, but generally accurate.

So, can the worst of the worst be depicted as anything other than evil in literature? Can their actions be explained in a way that allows the reader to understand them? One of the challenges of writing is to create situations and characters that readers can relate to, can identify with to immerse themselves in the writing and gain an understanding of the journey traveled by the protagonists. Can evil be explained. Understood?

“I like children, they are tasty,” Albert Fish told the police upon his capture. A cannibal and pedophile, Fish was charged with murdering three children and said his victim count could be up to 100 children. Can this be explained? Understood?

If one believes Douglas, Samenow and others, then the answer is “no.” But what can be understood, and in that understanding, can be explained by writers, is that humanity abides. That “good” which distinguishes most of us from the Kempers, Bundys and Fishes of the world is never extinguished or dulled by “evil.”

Humanity abides in the courage and life of Lisa McVey. She escaped the clutches of serial rapist and killer Bobbie Joe Long, and is today a deputy with the sex crimes unit at the Hillsborough County (Florida) Sheriff’s Office, and also works as a middle school resource officer. McVey was the victim of sexual abuse throughout her youth and was in and out of foster care to escape the home of her drug and alcohol-addicted mother. The night before her abduction by Long she was contemplating suicide and had written a suicide note. During her 26-hour captivity, torture and rape by Long, McVey memorized details about her kidnapper, his home, and left fingerprints in the bathroom to help identify her if she was killed. With her assistance, police were able to find Long and connect him to other crimes. He was tried, found guilty and eventually executed.

Humanity abides in Kate Moir who escaped from Australian serial killing couple David and Catherine Birnie. She has dedicated her life to championing for victims of violent crimes. Moir worked tirelessly to bring reform to Australia’s parole system so that violent criminals charged with three or more murders in one trial could be deemed ineligible for parole.

Humanity abides in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn a Russian dissident and novelist who raised global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, in particular in the Gulag system, a series of prisons and labor camps. He wrote a number of novels, including The Gulag Archipelago that exposed the torture and death in the Gulag. He was eventually forced to leave his own country. Solzhenitsyn was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature “for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature.”

It is impossible to understand the minds of monsters like Kemper, Bundy, Fish, Long, or the orchestrators of the Holocaust or the Gulag, but writers can find humanity and courage in people like McVey, Moir and Solzhenitsyn. They are a bright relief against the shadows of evil. When writing about the darker corners of life, there are always windows where light can be found to shine into those corners.

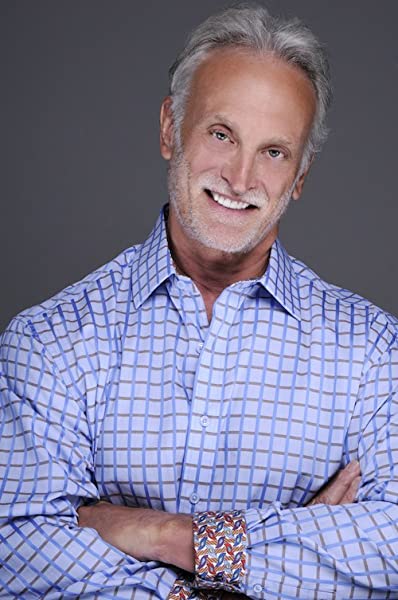

About the Author

John David Bethel is the author of award-winning novels, Unheard of and Holding Back the Dark. Other published novels include Little Wars and Wretched. He has also been published in popular consumer magazines and respected political journals.

Mr. Bethel spent 35 years in senior position in politics and government. He served as Senior Adviser/Director of Speechwriting for the Secretaries of Commerce and Education; Editorial Director for the U.S. Small Business Administration; and Assistant Administrator for the U.S. General Services Administration’s Office of Communications and Citizen Services. Bethel also worked as press secretary/speechwriter to Members of Congress.

Mr. Bethel is a senior consultant for a number of prominent communications management firms, including Burson Marsteller and The Wade Group.

He graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors from Tulane University and lives in DeLand, Florida.

True Crime Features

Southern Unsolved Mysteries

Three of the South’s Most Terrifying Unsolved Mysteries

Iconic Characters of True Crime

True crime characters that stand out more starkly than the rest

Real Life Monsters

The Appeal of True Crime: When Real Life Becomes a Monster Story