True Crime and Espionage

by David Adams Cleveland

It is sorely strange for a writer of fiction who has just spent four years writing a novel about the Alger Hiss spy case of the late 1940s—when Stalin’s KGB spies had penetrated the highest reaches of the US government—to find himself eerily reminded of those times by Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Ex-KGB operative Putin and his leadership circle have all the hallmarks (and the stink) of the old Soviet intelligence services as they try to sow discord and confusion among the ranks of their targeted victims—and failing that: brutal repression. A nightmare world of lies and fabrications, intimidation and fear has once again descended upon Russia and Ukraine in the guise of a new but very familiar Iron Curtain. Putin is a last disciple of Stalin’s methodology so aptly described by Alger Hiss’s accuser, Whitaker Chambers:

“For the temper of Stalin’s mind requires a strategy of multiple deceptions, which confuse the victim with the illusion of power, and soften them up with the illusion of hope, only to plunge them deeper into despair when the illusion fades, the trap is sprung, and the victims gasp with horror, as they hurtle into space.”

The voice of Whittaker Chambers, echoing down the wind, features prominently as an off-stage character in my latest novel, Gods of Deception, a man who understood Stalin’s malevolent modus operandi to his fingertips. Chambers, a Columbia University educated intellectual had first been drawn to Communism in the 1920s, writing for the New Masses and other Marxist publications in America—all virtual mouthpieces of Moscow’s party line. He then became an underground agent for Soviet military intelligence, or GRU, running a coven of spies in Washington including Harry Dexter White at Treasury and Alger Hiss in the State Department. But Chambers, a man of subtle intelligence and spiritual depths, soon realized the toxic nature of Stalin’s rule as the dictator began eliminating tens of thousands of his own supporters in paranoid purges during the late 1930s. Knowing his own life was in danger, Chambers broke with the Soviet underground in 1938; he then tried to break away the Washington spies he handled, thinking he’d broken White, but failing with Alger Hiss and his wife Priscilla, who dismissed him with an ominous threat: Stalin plays for keeps. Chambers bought a gun and fled with his family to a hideout in Florida before the KGB goons found him.

A year later, horrified by the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact of late 1939, which divided up Poland and started WWII, Chambers went to the highest security official in the State Department, Adolf Berle, and presented him with a list of Soviet agents in the US government that he had either handled or had known about. The list included Harry Dexter White and Alger Hiss. Berle went to Roosevelt with Chamber’s list of potential security risks but was dismissed with an expletive. And so White and Hiss and scores of other top officials, including another Soviet asset, Lauchlin Currie in the White House, remained in place during the Second World War, undermining US interests at every turn and laying the groundwork for Stalin’s depredations at war’s end.

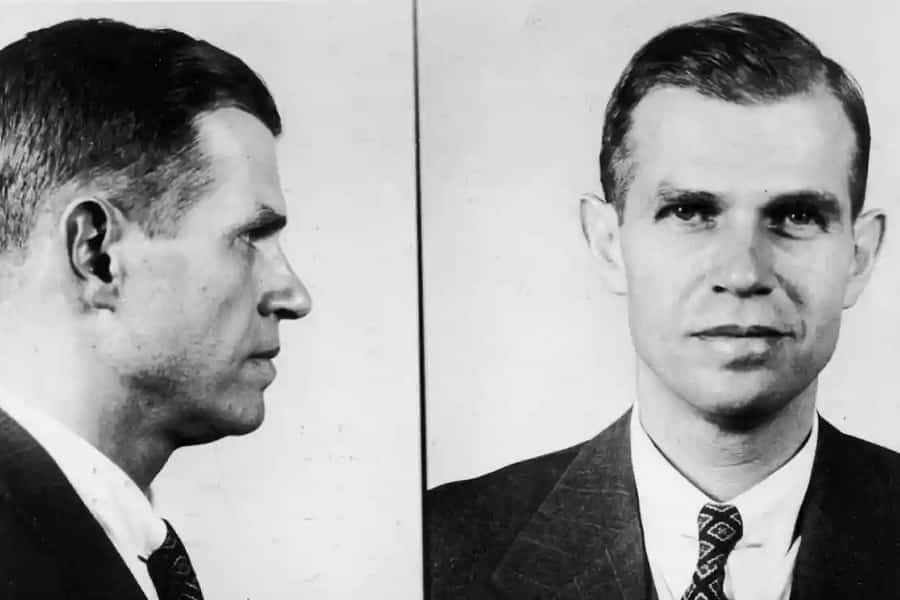

Astonishingly, Stalin’s agents might well have gone undetected if not for the defection of Elizabeth Bentley (the “Red Spy Queen”) in 1945. Disgusted with the Soviet underground and broken hearted by the death of her lover and KGB handler, Bentley went to the FBI with a list of 41 names, including those of White and Hiss. This broke the silence (possibly incompetence or criminal negligence) around Stalin’s infiltration of the US government and related war industries, galvanizing the FBI to unwind and root out what we now know to have been about 500 Soviet spies, including the Rosenbergs whose network of operatives stole US atomic bombs secrets and hastened Stalin’s acquisition of nuclear weapons by years. One of those agents, now ex-agent, was Whittaker Chambers, who, by the mid-forties, was a senior editor at Time Magazine and one of the few journalists in America who understood Stalin’s methodology and the dangers faced by the free word. Chambers, first interrogated by the FBI and later HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee), again named a list of Soviet agents including Alger Hiss (and his brother Donald) at State, Harry Dexter White at Treasury, and Lauchlin Currie who had been a White House advisor to Roosevelt. Hiss and the others vehemently denied the charges of spying and the FBI and HUAC were about to give up the case for lack of evidence, when Chamber’s was pressed into producing what he described as his “insurance policy,” a group of sixty-one top-secret State Department documents, some with Hiss’s handwriting, most typed on the Hiss’s Woodstock typewriter. Chambers had hidden these in a dumbwaiter in his brother-in-law’s home when he’d defected from the Soviet underground in 1938. The top-secret documents became famously known as the Pumpkin Papers since Chambers had hidden some additional microfilm in a pumpkin patch on his Maryland farm. This hard and seemingly irrefutable evidence was enough for the Justice Department to bring two charges of perjury against Alger Hiss: lying to a grand jury about when he’d known Chambers and for passing top-secret documents to Chambers.

As a writer of fiction, the subsequent “trial of the century” as it was called offered much grist for the mill: there were the Pumpkin Papers, the Hiss’s Woodstock typewriter that the FBI matched to the retrieved State Department documents, the defamation of Chambers’s character by the Hiss defense team—all fascinating subjects that lent themselves to fictional exploration. Perhaps the most extraordinary feature of the trial was how Alger Hiss and his wife Priscilla first refused to acknowledge that they’d ever known Chambers and his wife, either as his spy-handler alias, “Karl,” or by his real name. This when Chambers was able to describe a range of details about the Hisses that only an intimate friend would know, including the interior of their home, trips they’d taken together, bird watching (a passion they shared), and confidential conversations on a range of topics from international affairs to parenting. The Hiss’s black maid even testified that Chambers and his wife had had dinner with Alger and Priscilla in their home on Volta Place in Washington. Hiss finally admitted that he might have known Chambers but only under another alias—reminded, so he testified, by Chamber’s bad teeth!—and only for a short period and as a journalist who had wanted to interview him.

The Hiss defense team had only one real strategy: destroy Chamber’s credibility by destroying his character in the witness box. What a bizarre courtroom scene as Chambers testified in often colorful and exacting detail about his years collecting top-secret documents from the Hisses (copying them overnight and returning them before morning), while Alger and Priscilla Hiss denied everything. It was as if they lived in totally different worlds—parallel universes. In the end, it was the stolen State Department papers, typed on the Hiss’s typewriter, which convinced the jury. Even as Chambers’s character was besmirched beyond redemption in the eyes of millions. A subject which is taken up thematically in my latest novel.

For the most part, I kept the courtroom drama to a minimum in Gods of Deception, preferring to focus on how the Hiss trial divided the country for almost fifty years: half believing in the innocence of Hiss, the golden-boy of the Eastern establishment (somehow framed by Hoover’s FBI and enemies of the New Deal); half believing Hiss was a spy, and possibly worse—an agent of influence who sat at Roosevelt’s right hand at Yalta. What exactly, I asked myself, was at stake? And how could Alger Hiss have convinced so many of his innocence—including his defense team? In retrospect, it seems almost unbelievable that so many were taken in by Hiss’s lies. With the release in the late 1990s of once secret decrypted Soviet cable traffic from WWII (Venona), and a brief window of access to Soviet era intelligence files under the Presidency of Boris Yeltsin, we now know for a certainty that Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White, Lauchlin Currie and some 500 others were Stalin’s willing agents. Again, begging the question, how was Alger Hiss able to convince half the country and his defense team that he’d never known Whitaker Chamber as his spy handler, when Chambers testified in court with such compelling detail about their relationship, going on to write a bestseller, Witness, excerpted in the Saturday Evening Post, that told of his days as a Soviet agent in prose that often rose to the level of poetry? It seems that even Whittaker Chambers found Alger Hiss to be something of an enigma.

To explore this question, I settled on one of my main characters, Edward Dimock, the Judge, who, as a young lawyer, served as defense counsel for Hiss in the infamous spy trial. At ninety-five, the Judge is trying to finish his long-anticipated memoir about the trial and other matters. He enlists his grandson, George Altmann, a Princeton astrophysicist, to help him complete the manuscript, who discovers in the Judge’s files a number of letters from Priscilla Hiss, and an old corkboard with sketches of potential witnesses for the prosecution who either died mysteriously or ended up behind the Iron Curtain and so unable to testify. Through George’s and his grandfather’s eyes we are taken into the shadowy background of the Hiss case, while exploring answers to one of the most puzzling enigmas of the twentieth century: who was Alger Hiss? The man who, even after his conviction and a lengthy appeals process, and four years in prison continued to plead his innocence to his dying day—an Iago of cosmic depths. And so unlike the notorious British spies Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, and Guy Burgess who all ended up dying early of alcoholism in their Moscow exile. Hiss never let down his guard, suffered no remorse, and so remained a hero to his supporters to the end.

It is this mystery, among others, that George Altmann’s sleuthing uncovers within the pages of Gods of Deception—revelations that were even shocking for me to write about—not just a truth stranger than fiction, but one that changed the way I understood the history of the Cold War.

Just three instances will have to serve as an introduction to what is to be found in the pages of Gods of Destruction.

We now know that in 1941, Harry Dexter White, one of Chambers’s spies at the US Treasury, was contacted by Soviet agent Victor Pavlov, meeting at the Old Ebbitt’s Grill across the street from his Treasury office. White was handed a plan (known as Operation Snow) concocted by Stalin which called for the US to ratchet up pressure on Japan by imposing more sanctions on oil and raw materials—all to the end of precipitating a war in the Pacific against the US and its allies, instead of further Japanese aggression directed at the Soviet Union in the Far-east. White followed his instructions to the letter, producing policy papers that called for a more belligerent stance towards Japan, at precisely the moment when the US navy was advising a lessening on tensions towards Japan—and a potential Pacific war that the Navy was in no position to undertake, especially with the threat of Hitler on the horizon. White’s influence on US foreign policy may well have helped provoke the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, an attack that relieved Stalin and the Soviet Union of a feared second-front attack on their exposed Eastern flank.

When I began research for Gods of Deception, I figured that Alger Hiss was probably guilty for having passed top-secret State Department documents in the late 1930s (of little importance in the larger scheme of things). What I didn’t realize was that the real damage he did was as an agent of influence who sat at Roosevelt’s right hand at Yalta, where he helped prepare the legal documents that paved the way for Stalin’s domination of most of Eastern Europe and Poland. Each morning at Yalta, Hiss was debriefed by his Soviet handler vis a vis the US and allied negotiating positions. Later, returning with elements of the US team, Hiss stopped off in Moscow, where he was taken aside in a secret ceremony with the head of Soviet intelligence and presented with the Order of the Red Star.

Perhaps one of the most devastating revelations was the role of Soviet spy William Weisband, who worked in Army intelligence in Arlington, Virginia. US Army intelligence had broken the codes used by the Soviet military to communicate about the disposition of men and material. In 1949, Weisband tipped off his Soviet handler that the US Army was reading Soviet military communications. Almost immediately Soviet military communications went dark as they changed their codes, leaving US intelligence blind to the movements of Soviet weapons and logistics support to the North Koreans. And so the US was taken completely by surprise by North Korea’s June, 1950 invasion of the South, precipitating the Korean War in which fifty-thousand Americans died. But for William Weisband’s treachery, the US might have been able to prepare for the invasion—or warn off Stalin with pledges that the US would fight, and very likely have prevented war in the first place.

A sad story indeed, and a story which continues today as a new Iron Curtain—very much like the old—descends upon Russia and Ukraine. The gods (KGB) of deception are, sadly, still with us.

About the Author

David Adams Cleveland is a novelist and art historian. His previous novel, Time’s Betrayal, was awarded Best Historical Novel of 2017 by Reading the Past. Pulitzer prize-winning author Robert Olen Butler called Time’s Betrayal ”a vast, rich, endlessly absorbing novel engaging with the great and enduring theme of literary art, the quest for identity.” Bruce Olds, two-time Pulitzer-nominated author, described Time’s Betrayal as a ”monumental work . . . in a league of its own and class by itself . . . a large-hearted American epic that deserves the widest possible, most discriminating of readerships.” In summer 2014, his second novel, Love’s Attraction, became the top-selling hardback fiction for Barnes & Noble in New England. Fictionalcities.uk included Love’s Attraction on its list of top novels for 2013. His first novel, With a Gemlike Flame, drew wide praise for its evocation of Venice and the hunt for a lost masterpiece by Raphael.

He and his wife split their time between the Catskills and Siesta Key, Florida. More about David and his publications can be found on his author site: davidadamscleveland.com.

Espionage Features

Southern Unsolved Mysteries

Three of the South’s Most Terrifying Unsolved Mysteries

Iconic Characters of True Crime

True crime characters that stand out more starkly than the rest

Women in Spy Novels

The golden era of female protagonists in espionage fiction